Barbara Aiello, who calls herself Italy’s first female rabbi, runs a synagogue associated with Reconstructionist Judaism. According to Italy’s Jewish community, she represents only herself.

Georgia L. Gilholy

(JNS)

In the heart of Italy’s southern region, Calabria, Rabbi Barbara Aiello has been working to revive a forgotten legacy—the Jewish communities that persisted there from the Maccabean era until the 16th-century Inquisition.

Her efforts have been neither without challenges nor controversies.

Calabria’s captivating landscapes and historical significance belies its forgotten Jewish history. Aiello, a U.S. expatriate, has spent nearly two decades nurturing a vibrant community in an area that she claims was about half Jewish under the Inquisition.

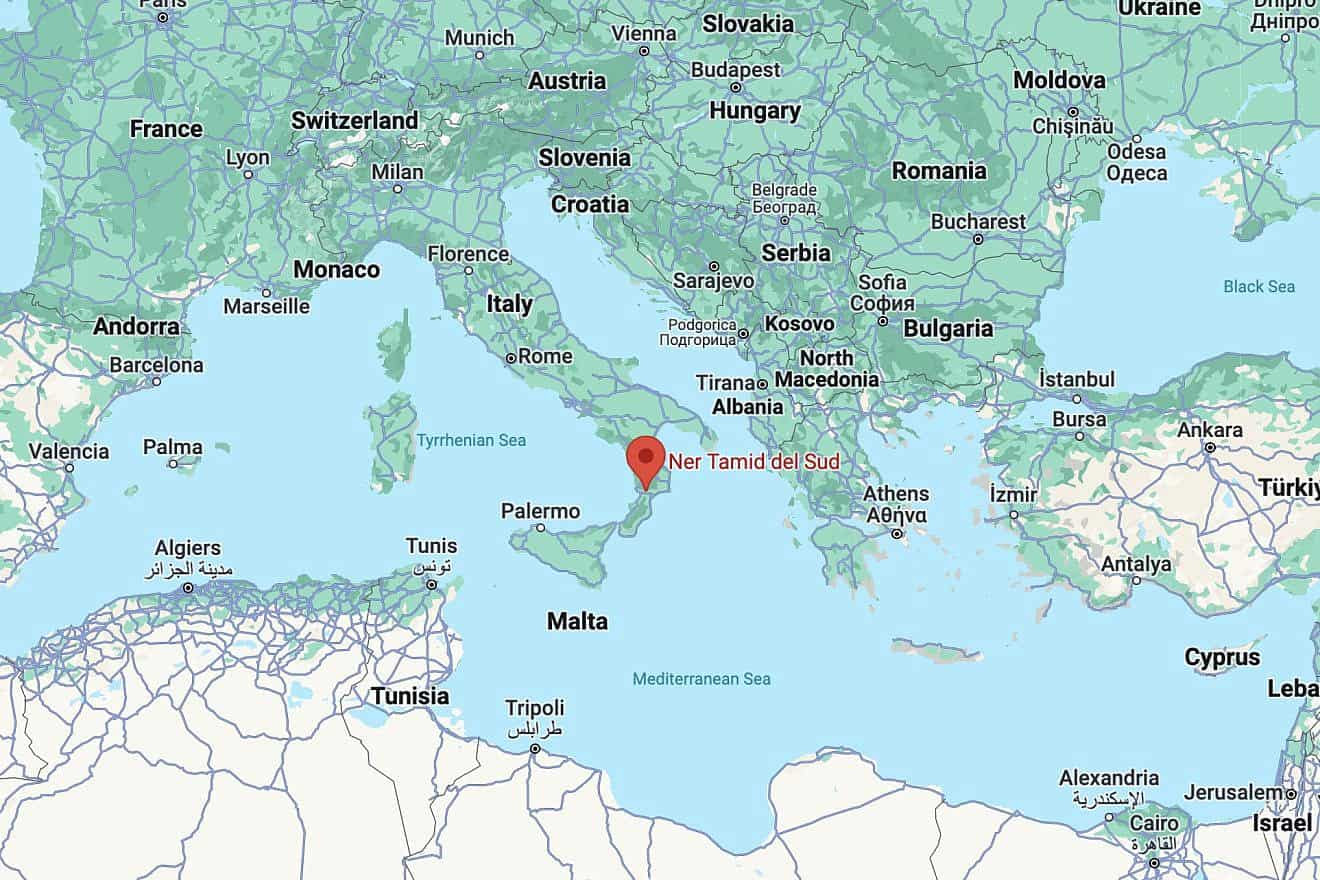

When the community dedicated Sinagoga Ner Tamid del Sud (“Eternal Light of the South”) in the town of Serrastretta in 2006, that was the region’s first synagogue in centuries, Aiello told JNS. The synagogue is affiliated with the Reconstructionist Jewish movement.

“We expanded it in 2014. And why did we expand it? Because our congregation is bnei anusim, descendants of Sephardic Jews, who were forcibly converted to Christianity,” she said.

The bnei anusim—“children of those forced to convert,” a term that many prefer to marranos, “pigs”—exist in a kind of organizational limbo. Many identify as Jews and feel very Jewish, but official Jewish communities and rabbinic authorities often do not see them as such, often due to uncertainties over generational distance and problems proving direct maternal Jewish lineage.

But this group is at the heart of Aiello’s mission.

“Many of our members have found their way back to their Jewish roots and are eager to reconnect with their heritage,” she told JNS. “Others have discovered their Jewish roots but are not in a position to convert. Others simply say, ‘I’m not going to convert because I was never anything else.’”

‘Not a real rabbi’

Aiello says her synagogue is a haven for those who need a supportive community and who want to rediscover their ancestral identity. But her progressive approach, and being a woman rabbi, have sparked resistance from some Orthodox communities, she told JNS.

“We face claims that we are not a real synagogue. Not a real rabbi,” she scoffed. “In fact, we have a very robust conversion program and a local community.”

The congregation has been criticized as just another synagogue for expats to come to for a bar mitzvah or a wedding, according to Aiello. “It’s just ridiculous,” she said.

“We are a real synagogue with a real membership,” she said.

Orthodox communities in Italy do not formally recognize Aiello’s community, which accepts same-sex and interfaith marriages, highlighting division within the Jewish landscape in Italy and beyond.

The rabbinical office and council of the Naples Jewish community sought to cancel a 2021 event, during which Aiello was slated to speak with a representative of the ecumenical activities secretariat. The Naples community cited her non-Orthodox credentials, Aiello told JNS.

The talk went forward, but the conference was “tainted” by the exchange, exacerbated by the fact that Aiello was the first speaker, she told JNS. “Sometimes, I tire of the fight,” she said.

‘She can represent only herself’

The nearly 115-year-old Union of Italian Jewish Communities is Italy’s central Jewish body, and UCEI’s president since 2016 is the Jerusalem-born Noemi Di Segni.

“Today, there are 21 Jewish communities in Italy and also sections of communities—small Jewish representations that operate within the jurisdiction of a certain community—and they are all gathered under the legal representation of the Union of Italian Jewish Communities, Di Segni told JNS.

“Italian Judaism has always followed the line of tradition and observance of Orthodox ritual norms, which have kept it alive and unitary over the centuries,” she added.

Italian law, which is based upon a 1987 agreement between UCEI and the Italian state, regulates Jewish communities in the country, according to Di Segni.

Religious and daily affairs are regulated by halacha, rabbinic law, “according to the rabbinical competencies, in the union or the single communities, according to the Orthodox tradition,” Di Segni said.

She added that Italian law allows for establishment of new official Jewish communities through an “exact procedure that is dictated in the law and in the bylaws that are recalled in the same law.” Recognition also requires a presidential decree.

“It cannot be established on the basis of a personal, private act of a group of persons that decides for their own interest to establish a community,” she said. “Of course, they are free and can establish an association, have cultural and religious activities, have fun or discuss political thorny issues, but a Jewish community in the formal, public and legal relevance is a different thing and needs to respect the legal procedure.”

No one is saying that non-official Jewish communities are operating illegally, “but surely they cannot be considered a formal community, and by using this denomination making others think that they are the formal community,” Di Segni said. The Jewish community of Naples is the official, government-recognized Jewish community, and it has “competency over the south of Italy.”

There are fewer than five Jews, per Orthodox tradition, living regularly in the city of Catania—just southwest of Calabria—and they are part of the Naples community. Efforts to claim that there is a distinct official Jewish community in that area are misleading, she said.

A committee within the UCEI, the Consulta Rabbinica, appoints official rabbis in Italy, and it has not done so with Aiello, according to Di Segni. “She can represent only herself and her religious stream, but surely she is not appointed to any Jewish community in Italy—not even to the Catania one,” she said. “Our duty is to ensure that the Italian public and institutions are mindful of the persons that they call to hear and invite as speakers.”

Anyone is free to earn money teaching courses of speaking on the radio or on television, and the UCEI doesn’t censor anyone. “This is unthinkable in Italy,” Di Segni said. But she added that legally, Aiello “cannot claim that she represents Italian Judaism formally.”

‘Foolish to deny our existence’

The 2021 row was not the only time that Aiello had felt pushed out.

In March, she received about 50 emails asking why she hadn’t been invited to nor attended a large conference on Calabria’s Jewish roots, held in Nicotera, in Calabria.

“It’s foolish to deny our existence, let alone our efforts for the Jewish community outside the synagogue,” she told JNS. She noted that her synagogue has a program in which its representatives talk about the Holocaust and antisemitism at local schools.

Some 17 years ago, Aiello told JNS that she was riding in a taxi en route to Calabria’s Lamezia Terme International Airport to fly to Rome to appear on a television program when a producer called and told her not to come to the studio. She asked repeatedly for the reason, but the producer wouldn’t say, she told JNS.

“Later, I heard from a colleague that the cancellation was probably the result of the UCEI hearing of my appearance and convincing the television program not to have me participate,” she told JNS.

She added that the UCEI doesn’t recognize Gilberto Ventura, the Brazilian-born rabbi who operates in Catania. “He is an orthodox rabbi,” she told JNS.

Angela Yael Amato, a violinist with a family history in both Calabria and Sicily who is a board member at Aiello’s synagogue, told JNS that she is part of the Italian communities “through the teshuva process.” (Teshuva means repentance.)

“We widely participate in her liberal Jewish community work,” Amato told JNS. “The problem of accepting the liberal movement in Italy is because the Orthodox tradition does not accept women rabbis or interfaith marriages.”

“It seems that in Italy there are several bureaucratic issues regarding the possibility to do that,” she added.

Featured Image: Six people — including two ‘bnei anusim’ — immersed in the Mediterranean Sea after sitting before the three-rabbi Calabria Bet Din in southern Italy. Courtesy: Rabbi Barbara Aiello.